Written by: Ms. Arge Louise Joy Esquivel, EnP

Known for its stone houses perched atop postcard-perfect cliffs, where emerald grass meets the rhythmic crash of waves against volcanic boulders, Batanes feels like a landscape touched by divine forces. Yet, it is perhaps for that very reason that the islands endure the fury of nature more than most.

In May 2025, researchers from the UP Resilience Institute traveled to Batanes to engage with the Ivatans, whose deep understanding of their environment has allowed them to thrive amid constant climatic challenges. The visit was part of the project “Bridging Academic Researchers and Vulnerable Island Communities in the Philippines: Enhancing the Climate and Disaster Risk Management Capacities of Municipalities in Batanes” (APN–Batanes Project), which aims to set the stage for scientific and traditional knowledge to co-exist, especially in resilience building.

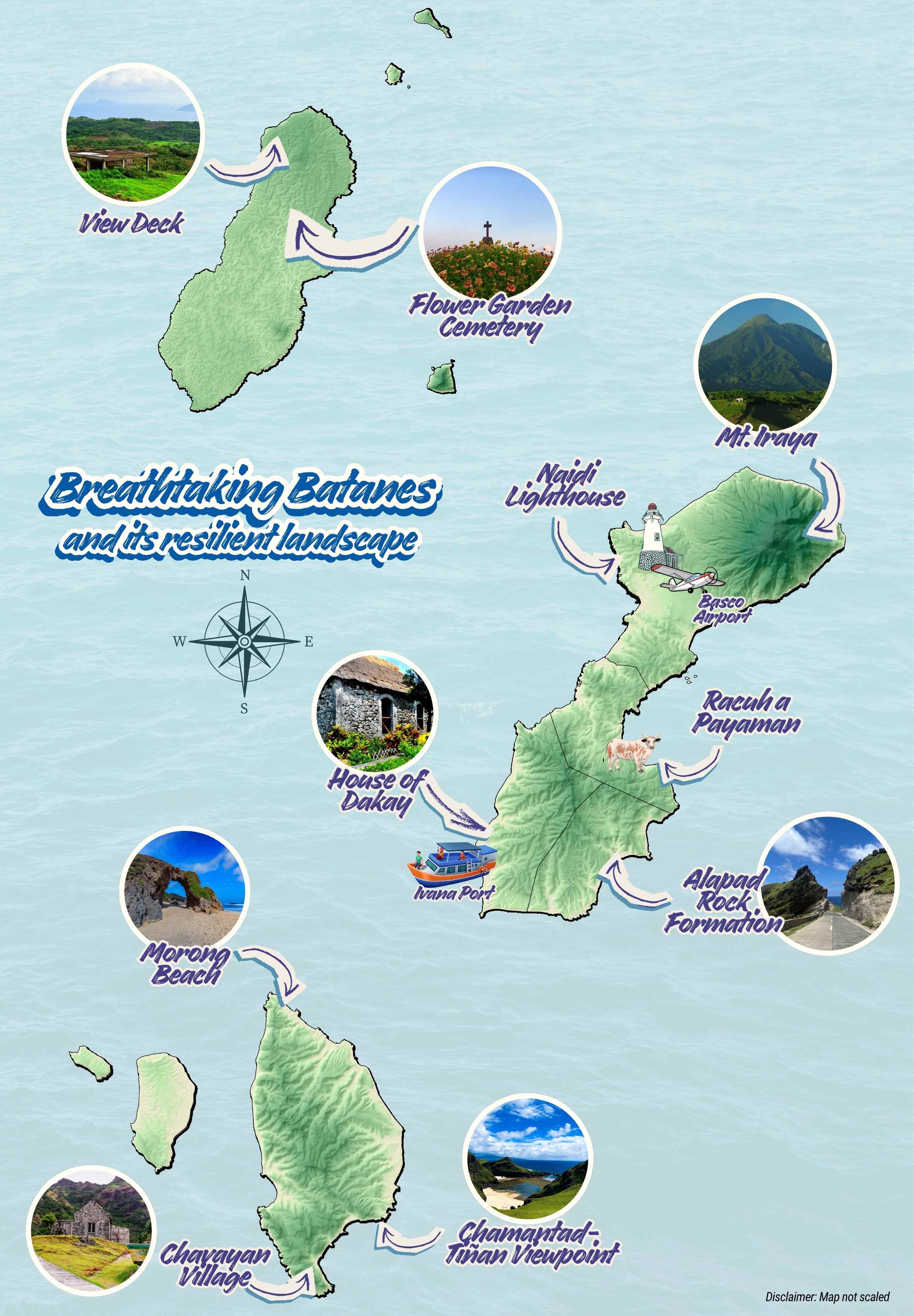

Batanes consists of six local government units: four located on Batan Island and two — Sabtang and Itbayat — each on their own islands. Across these distinct yet interconnected communities, the project documented how traditional knowledge, adaptive architecture, and community cohesion form the foundation of local resilience.

This article explores selected tourism destinations across the six municipalities, uncovering how each site reflects the stories of Ivatans’ resilience and their enduring relationship with their land and seascape. Beyond serving as tourist attractions, these places stand as tangible expressions of the community’s resilience in the face of a changing climate.

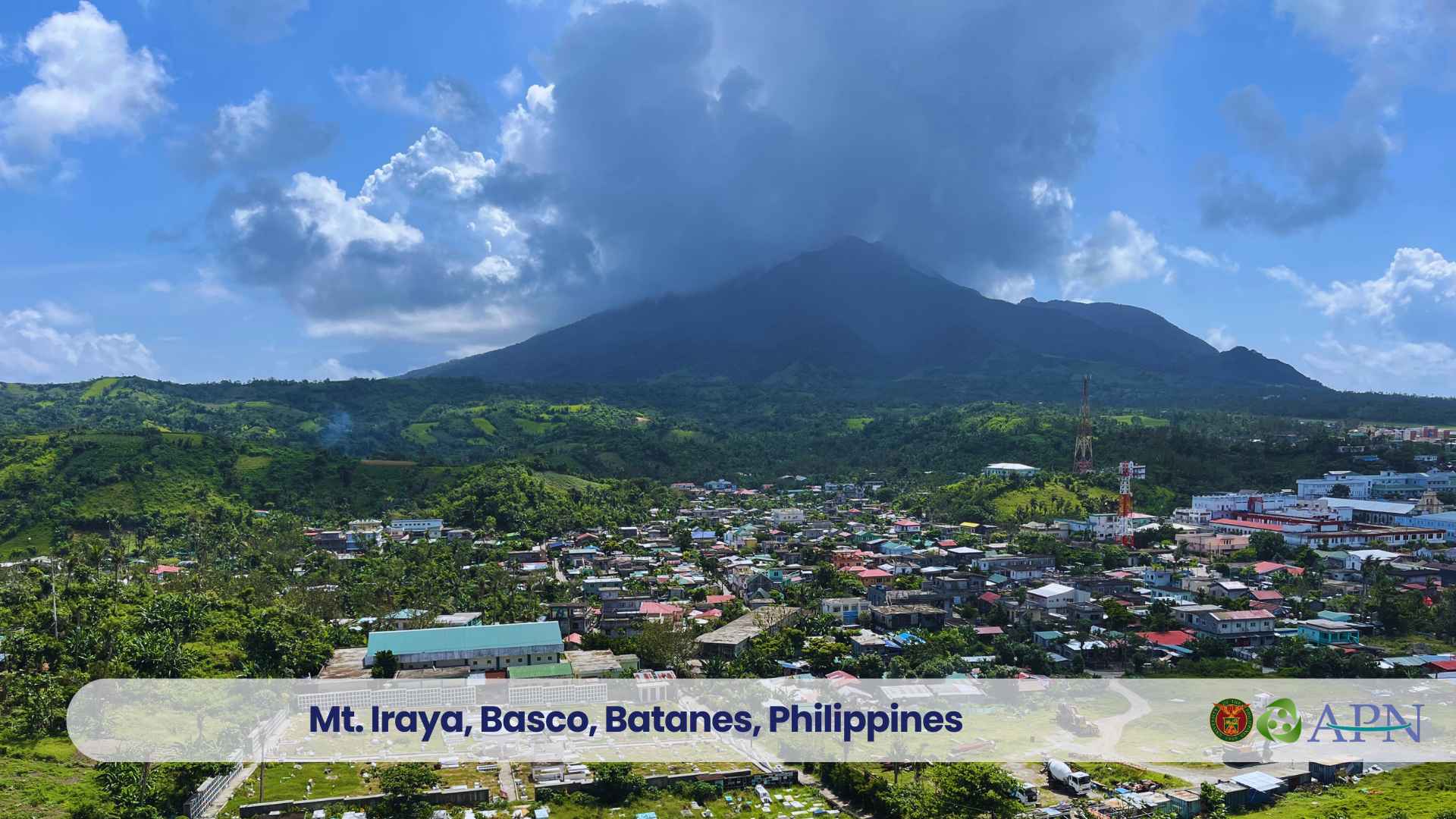

Basco: Mt. Iraya and Lighthouse

Mt. Iraya, classified by PHIVOLCS as an active volcano[1], last erupted in 1454[2]. For the Ivatans, it is regarded as a sacred site—an enduring presence that shapes both their landscape and way of life. The mountain’s slopes are abundantly surrounded by vutalaw (Calophyllum inophyllum)[3], a native windbreak tree that shields the cultivated fields of Batan. These trees are well cared for, especially near Racuaranum, the biggest spring found in the northern part of Iraya. To the Ivatans, the volcano is not a destructive force but a powerful being deserving of respect. Their reverence is matched by preparedness, as they live in harmony with the knowledge of its eventual awakenin

Nearby, Basco Lighthouse offers panoramic views of the West Philippine Sea, the Basco townscape, and rolling hills. The Basco lighthouse, alongside the other lighthouses across the province, is crucial for maritime safety and national sovereignty[4]. They act as navigational aids for local fishermen and thousands of foreign vessels, warning them of the island’s rocky coasts and guiding them to shore, especially at night. Beyond their functional role, they are also important cultural symbols and tourist attractions that highlight Batanes’ heritage and picturesque landscape.

Mahatao: Marlboro County

The entire province of Batanes was declared a protected area through Republic Act (RA) 8991 or Batanes Protected Area Act of 2000 to safeguard its outstanding natural and cultural heritage. At the same time, it remains the ancestral land of the Ivatans, as recognized by the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997 (RA 8371). These complementary legal frameworks work together to conserve the environment while upholding the ancestral rights of the local people. They may restrict certain activities, but they also ensure that the islands’ landscapes are managed sustainably and remain in the hands of the local people.

Land ownership in Batanes is notably distinct. Section 7 of RA 8991 recognizes lands occupied by Ivatan families since time immemorial and allows their disposition, including partible inheritance, where property is divided among heirs. Meanwhile, Section 10 of IPRA Law upholds that ancestral lands cannot be unlawfully claimed by non-Ivatans. Land tenancy does not exist—each household manages its own land[3]. This autonomy allows Ivatans to plan, cultivate, and prepare their properties with long-term resilience in mind. Their traditional agroforestry systems demonstrate this wisdom through vutalaw trees that serve as natural fences and windbreaks, protecting crops from strong winds that sweep across the hills[3].

With its rolling green pastures and open horizons, Marlboro Hills—or Racuh a Payaman—embodies the harmony between people, land, and livestock. Here, cows, carabaos, and horses roam freely across the grassy slopes. The government permits the use of the pasturelands for locals who wish to raise their animals, reinforcing a shared sense of stewardship over the landscape. From the vantage point of Marlboro Hills, one can see how the Ivatans make the most of their terrain: while rice is still cultivated in small plots, it is not widely grown because of the typhoons and uneven terrain. Instead, root crops like yam, sweet potato, taro, garlic, and onions dominate the fields[3].

Ivana: House of Dakay and the Spanish Bridge

From the rolling hills of Mahatao, the road leads to the quiet town of Ivana. The House of Dakay, built in 18875, is the oldest surviving stone house in Batanes. Its thick limestone walls and cogon roofs have endured countless typhoons and earthquakes. Inside, the wooden floors creak softly, carrying the memory of generations that once sought shelter within its sturdy frame. The house stands as a living symbol of Ivatan resilience — simple, strong, and deeply connected to the land.

From the rolling hills of Mahatao, the road leads to the quiet town of Ivana. The House of Dakay, built in 18875, is the oldest surviving stone house in Batanes. Its thick limestone walls and cogon roofs have endured countless typhoons and earthquakes. Inside, the wooden floors creak softly, carrying the memory of generations that once sought shelter within its sturdy frame. The house stands as a living symbol of Ivatan resilience — simple, strong, and deeply connected to the land.

A short walk from the House of Dakay is the Spanish Bridge, built during the Spanish colonial period[6]. Made of stone and lime, the bridge still arches gracefully over a small stream, a quiet reminder of Batanes’ shared history with Spain. While it no longer functions as a bridge for vehicular access, it serves as a reminder of the craftsmanship and durability of Ivatan builders.

Nearby, the famous Honesty Coffee Shop welcomes visitors with its doors wide open and no one behind the counter. Here, customers take what they need and leave their payment in a small box. The shop has become a symbol of the Ivatan way of life, built on trust, honesty, and mutual respect.

Uyugan: Mutchong Viewpoint and Alapad Hills

At the southernmost tip of Batan Island lies Uyugan. The landscape is a tapestry of green pastures, winding coastal roads, and endless horizons. From the Mutchong Viewpoint, travelers are greeted with a sweeping view of farmlands dotted with grazing animals and a rugged coastline sculpted by the wind and waves—scenes that capture the quiet strength and enduring beauty of Batanes.

One of Uyugan’s most striking landmarks is the Alapad Rock Formation[7][8], an inclined rock face along the coast of Imnajbu, shaped over centuries by strong currents and tectonic shifts. Here, two massive rocks split apart naturally, leaving a gap that now accommodates a stretch of the island’s highway. The contrast of solid rock and the restless ocean makes Alapad a favorite stop for travelers seeking both drama and serenity in the landscape.

Though remote, Uyugan remains accessible through Batan Island’s circular road system, which links it with Mahatao, Ivana, and Basco. Public transport is limited—jeepneys from Basco make trips to the southern towns, often stopping along the way to pick up passengers and supplies. There is no fixed schedule; the journey begins when the jeep is full. For many Ivatans, motorcycles serve as their lifeline, allowing them to navigate the long coastal stretches and respond quickly when the weather shifts suddenly.

Other parts of Uyugan that were not explored by the team were the Long-Range Aid Navigation (LORAN) station and Sitio Song-song. The LORAN station was built by the Americans during World War II[7][9]. Sitio Song-song was once a settlement in Batanes that was devastated by a tsunami in 1950s[7]. The ruins standing along the coastline of Batanes remind us of the disastrous event that relocated the whole community.

Sabtang: Savidug and Chavayan Villages

From the main island, a short boat ride from Ivana Port brings you to Sabtang. In Savidug and Chavayan Villages, traditional stone houses stand close together, their thick limestone walls and cogon roofs built to endure the island’s fierce winds. Women weave vakul, a headgear made from dried palm fibers, while men repair boats along the shore. In urgent times, the tribal council gathers in a kamadid (hut), and the panintinan (a hanging iron bell) is rung to call the people or warn them of danger. This simple but effective early warning system shows how deeply the Ivatans value unity and preparedness. One remarkable sight is the limuniti, an indigenous anchoring device used to pull boats ashore[10]. It makes docking easier on the rocky coast, though it takes several people to operate. The teamwork needed for this task mirrors the cooperative and patient Ivatan way of life.

Even their food tells a story of resilience. The Ivatan cuisine was born from necessity—shaped by isolation, strong winds, and rough seas. Luñis is pork slow-cooked in rock salt until the fat renders, then stored in its own lard to last through stormy months[11]. Dibang, a flying fish, is salted and dried for preservation. What I liked the most was vunung, a communal meal whose name comes from kapayvunung, meaning “sharing.” It is served to guests, relatives, and friends who join in a celebration. The meal is wrapped in kabaya (breadfruit) leaves instead of banana leaves, since banana plants are often damaged by storms. Inside are turmeric rice, luñis, dibang, and uvud—a dish made from banana pith[12]. When a family is in need, neighbors lend a hand, and vunung is shared as a gesture of gratitude. These dishes are more than sustenance; they reflect the Ivatan way of life—anchored in foresight, strengthened by community, and sustained by a deep respect for nature.

Itbayat: Coral Island

The final stop is Itbayat, the northernmost inhabited island of the Philippines. Unlike the rest of Batanes, which is volcanic in origin, Itbayat is a raised coral island that rises hundreds of meters above the sea[13]. Reaching it requires courage. Boats dock against steep limestone cliffs, and visitors must climb concrete steps carved into the rock before setting foot on the island.

Itbayat’s Public Cemetery and Brgy. Raele Cemetery is very unique. Unlike most cemeteries marked with crosses, each burial site here is adorned with flowers. The sight is both humbling and profound — a quiet tribute to lives lived in harmony with nature. From this cliffside resting place, the vast sea stretches endlessly, reminding travelers that in Batanes, life and death both remain close to the elements.

The island’s geology is truly unique. Its relatively flat terrain offers a breathtaking 360-degree view of the ocean from the two-storey view deck. From this vantage point, you can see Ditarem, A’li, Siayan, and Di’nem Islands surrounding the main island. In the far north—beyond what can be seen from the island—lie Mavulis and Misanga Islands, located very close to Taiwan.

Life in Itbayat is the most difficult during stormy seasons. Its isolation makes the delivery of food and basic goods a constant challenge. Supply boats are often delayed by rough seas, especially during long storms when they cannot reach the island at all. According to the locals, they sometimes go weeks without new shipments of rice or corn. During these times, they depend on local produce and shared resources from neighbors. According to Itbayat locals, among the wide array of food that they utilize are the herb, hayud, and the breadfruit (kabaya in mainland Ivatans and atipuku in Itbayat). As the northernmost municipality in the country, help from the mainland or abroad rarely arrives quickly. Yet, the people of Itbayat endure with quiet strength. Their collective patience, resourcefulness, and unity reflect the adaptive capacities that characterize the resilience that defines all of Batanes — a resilience shaped by geographic isolation and strengthened by community cooperation.

What Makes Batanes Seascape and Landscape Resilient?

Despite being constantly battered by storms, the Batanes landscape and seascape continue to embody enduring beauty and strength. This resilience is deeply rooted in the Ivatans’ respect for their ancestral land and their long-standing commitment to living in harmony with nature. When tropical cyclones sweep across their island, the same land that they care for offers them protection and sustenance in return.

The tourism destinations across Batanes reflect this spirit of resilience in tangible ways. The stone houses symbolize the Ivatan’s ingenuity in designing structures that can withstand strong winds. The rolling hills show how careful land management prevents casualties from landslides. The coastal islands, while isolated, has strengthened local cooperation and resourcefulness.

However, the Ivatans are not exempt from the growing challenges of a changing climate. They have begun to observe shifts in their daily lives—dwindling supplies during prolonged storm seasons, increasing damage to houses and trees, and unpredictable weather patterns that affect their livelihoods. These experiences reveal how even communities that have adapted for centuries must continue to evolve as environmental conditions change.

Through the APN–Batanes Project, researchers—such as I—realized that resilience is not built overnight nor imposed from outside. It is cultivated through generations of understanding the land, the sea, and the climate that define daily life. Each destination, beyond its scenic appeal, tells a story of adaptation. At the same time, the experience reinforced a humbling truth that the practices that sustain communities today must continue to adapt to the uncertainties of tomorrow.

https://wovodat.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/volcano/erupt-history?volcan=595&sdate=&edate=&btn-search= [2] Global Volcanism Program, 2024. Iraya (274060) in [Database] Volcanoes of the world (v. 5.2.1; 3 Jul 2024). Distributed by Smithsonian Institution, compiled by Venzke, E. https://doi.org/10.5479/si.GVP.VOTW5-2024.5.2 [3] Blolong, R. R. 1996. The Ivatan cultural adaptation to typhoons: a portrait of a self-reliant community from the indigenous development perspective. [4] Mangosing, F. (2022, December 12). 4 new lighthouses, Coast Guard presence elate Batanes folk. Inquirer News. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1704045/4-new-lighthouses-coast-guard-presence-elate-batanes-folk [5] Department of Tourism. (2025, March 27). Visiting the House of Dakay, a timeless Ivatan treasure. [Facebook post]. https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1D7Fk6WJnV/ [6] Heritage and Tourism Office of Batanes. 2023. San Jose Spanish Bridge. In Breathtaking Batanes. https://breathtakingbatanes.com/Ivana [7] Guide to the Philippines. n.d. Information about Alapad Rock Formation. https://guidetothephilippines.ph/destinations-and-attractions/alapad-rock-formation [8] Abellera, R. J. 2014. Unbelievable Uyugan: spots you shouldn’t miss. https://www.rjdexplorer.com/unbelievable-uyugan-spots-you-shouldnt-miss/ [9] National Museum of the Philippines. (n.d.). Batanes. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/our-museums/regional-area-and-site-museums/batanes/ [10] Enego, R. M. (2025, October 24). Personal communication [Messenger correspondence]. [11] Abuso, G. (2024, November 18). Living with Typhoons: Lessons from the Ivatans of Batanes, Philippines. In Heinrich Boll Stiftung Southeast Asia. https://th.boell.org/en/2024/11/18/living-ivatans-philippines [12] Mendoza, H. (2025, September 6). Bite into Batanes: A journey through Ivatan cuisine. In The Benildean. https://thebenildean.org/2025/09/bite-into-batanes-a-journey-through-ivatan-cuisine [13] Bellwood, P. Dizon, E. Mijares, A. S. B. 2013. Archaeological Excavations on Itbayat and Siayan Islands. In book: 4000 Years of Migration and Cultural Exchange (Terra Australis 40): The Archaeology of the Batanes Islands, Northern Philippines. DOI: 10.22459/TA40.12.2013.02