by: Gereka Marie N. Garcia, Aira Joy C. Delos Angeles, Klara Rosan R. Bilbao, Dr. Dj Darwin Bandoy, Julia Fye S. Manzano, Keanu John A. Pelitro, Troy Owen P. Matavia, Kylone P. Soriano, Erika Elaine F. Muñiz, Jo Ann Camacho-Reyes, and Lira Angelo M. Cabrera

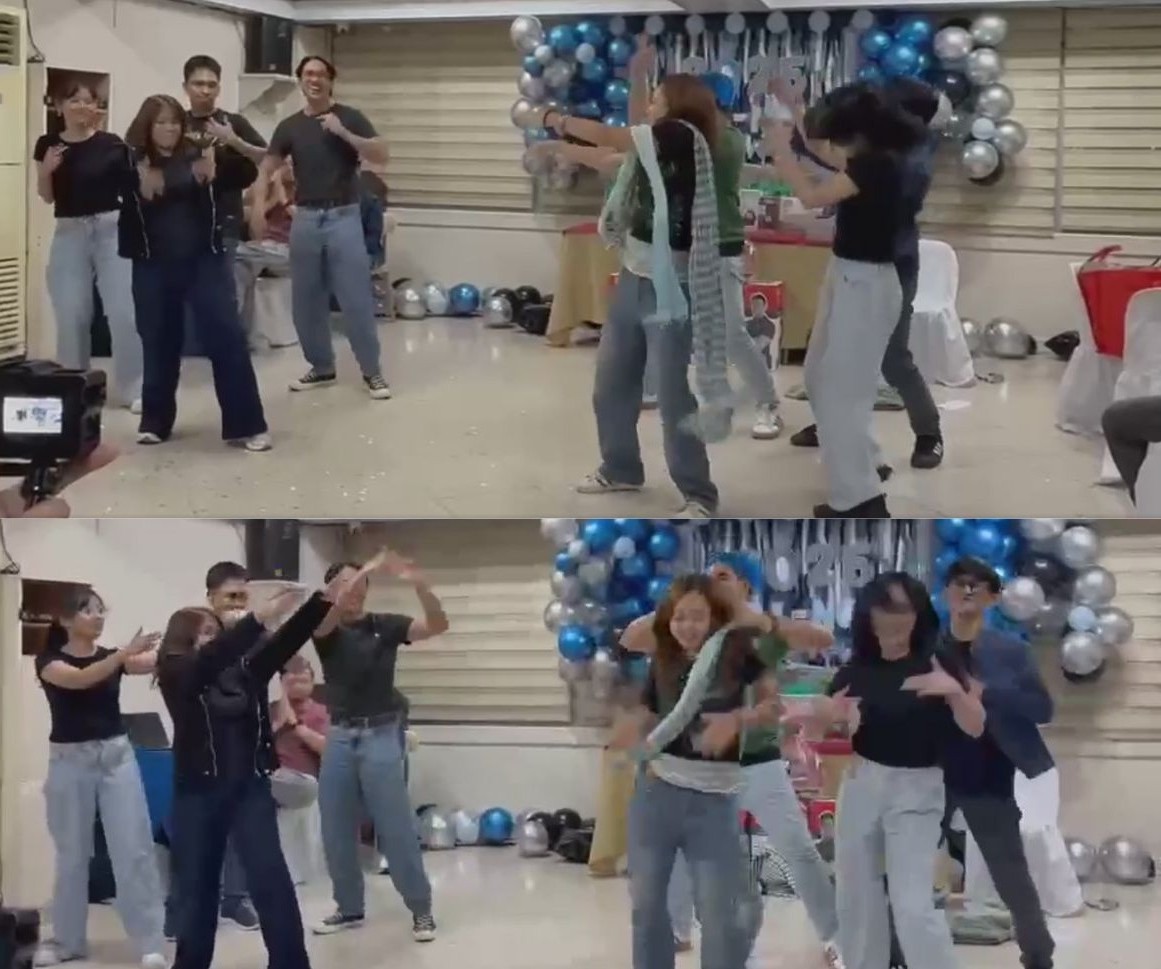

The UPRI – Research and Creative Works Division won first place at the annual UPRI Christmas party with a comedic performance that wove together pop culture, disaster politics, environmental critique, and institutional self-reflection—creating a show that was simultaneously accessible, humorous, and critical.

The story follows the Zaragoza family navigating everyday life and engaging with local authorities like Mayor Daddy Ko, whose infrastructure promises contrast with the looming threats mapped by UP NOAH. As floods and typhoons arrive, the family balances worry with humor, ultimately being saved by the mythicized Sierra Madre confronting Typhoon Uwan. Through music, pop culture, and playful storytelling, the performance concludes on a note of resilience, highlighting the ongoing fight for climate awareness and disaster preparedness.

At first glance, Pamilya Zaragoza reads as playful parody: exaggerated characters, budots beats, and cartoonish arcs. However, beneath the laughter lies a layered critique of Filipino experiences of climate risk, development promises, flood control, mythic protectors, AI, and science-based technologies.

Humor, Pop Culture, and Power: Bakhtinian Perspectives on Performance

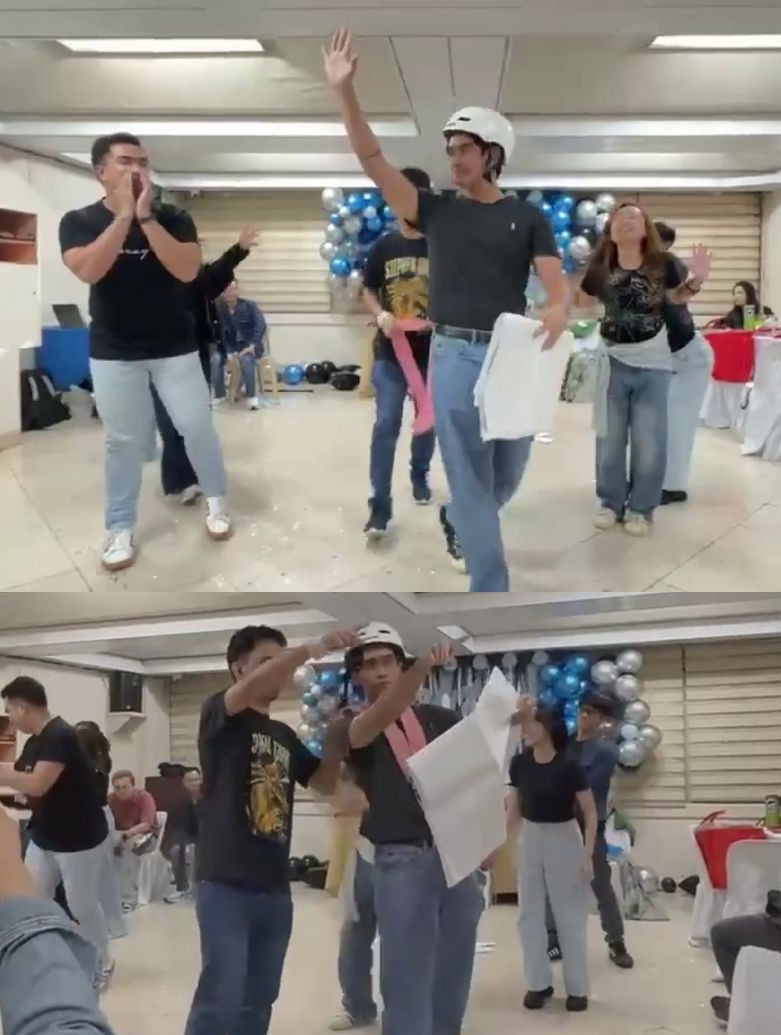

An ecstatic welcome as Mayor Daddy Ko arrives in town, greeted with excitement by the Zaragoza family.

The skit draws heavily on pop culture, Encantadia, K‑pop, budots, and TikToks – as a shared vernacular that bridges everyday experience and complex social issues. Through Bakhtin’s lens of heteroglossia, these references create a multiplicity of voices, expert discourse, and popular humor into a language the audience immediately understands.

The interplay of these cultural markers collapses the distance between formal climate governance and lived experience, bridging climate into an accessible dialogue that resonates with the community’s shared memory and understanding. By invoking familiar cultural touchstones, the performance encourages the audience to see their own social realities reflected and negotiated within the humor, creating a space where multiple perspectives coexist and interact.

Perhaps its most daring character is Mayor Daddy Ko – a caricature of politicians who embodies the archetype of the ‘development-driven’ politician whose grand promises of infrastructure and flood control carry both comedic and uneasy recognition. In Bakhtinian terms, the humor is carnivalesque: it temporarily suspends social norms, allowing parody, exaggeration, and multiple registers of speech to question authority and governance without directly confronting it.

Language here is deeply tied to social life and ethics: the skit highlights the moral stakes of governance, responsibility, and disaster preparedness, showing how humor, when framed through the carnivalesque, can serve as a socially and ethically engaged tool for understanding climate risk and collective resilience.

Sierra Madre vs. Uwan: Myth, Memory, and Environmental Loss

The climax features the viral AI-generated audio of Sierra Madre versus Typhoon Uwan, portraying the personified Sierra Madre confronting the storm. As typhoons recur, the refrain “Salamat, Sierra Madre” spreads on social media, connecting enduring folkloric traditions with the modern worlds of AI, short-form videos, and digital virality. These references are intentional: UPRI-RCW uses performance to link mythic imagination with contemporary media, making environmental risk both tangible and relatable.

The confrontation between Sierra Madre and Uwan transforms environmental science into mythic performance – not to escape reality, but to make it more tangible. Sierra Madre is framed as a maternal protector, echoing indigenous and folkloric understandings of nature as a living, relational entity, much like spirits in Filipino folklore that communicate moral or social truths.

Typhoon Uwan’s taunts, mocking sacrifice, neglect, and misplaced reliance, resonate like warnings embedded in collective memory, reminding audiences that society often expects nature to protect people even as it is degraded, deforested, and ignored. Echoing Mojares (2022). “Folklore is inherently positional, as the telling, understanding, and expression of folklore shape how people perceive and make sense of the world”. Here, the skit uses myth and performance to shape collective understanding of environmental precarity.

Drawing on folklore studies, this scene functions as a subversive narrative that critiques human-environment relations. By mythicizing Sierra Madre, the skit channels cultural anxieties and historical experience into a moral lesson: resilience is not automatic, and environmental loss carries ethical consequences. The performance makes visible what statistics alone cannot; it dramatizes a moral exchange, where nature’s “hauntings” serve as reminders of ecological precarity. Embedded within folklore, the narrative preserves collective memory of disasters—both human-made and natural—while fostering reflection on ethical responsibility, social accountability, and sustainable stewardship.

Why the Laughter Matters

Pamilya Zaragoza succeeds because it understands something essential about Filipino audiences: humor is not an escape from crisis; it is a way of surviving it. Laughter opens space for reflection. It disarms defensiveness. It allows hard truths to be spoken without alienation.

In a Christmas party setting, where joy is expected and seriousness is often unwelcome, the skit managed to do both. It entertained, but it also lingered. Long after the budots faded, the questions remained: Who really protects us? What do we trust: promises, myths, or each other? And what does resilience demand from those in power?

Winning first place was a recognition of performance quality. But the larger achievement of the University of the Philippines Resilience Institute – Research and Creative Work (UPRI-RCW) division’s Pamilya Zaragoza lies elsewhere: it offered a glimpse of what the division brings to UPRI, showing how art, creativity, pop culture, and humor can become vehicles for climate critique. The skit made the storm visible, and survivable – through shared laughter, demonstrating that creativity and critical engagement can go hand in hand.